Do you remember: Arctic politics in September

Russia and China exercise, the Nordics bond together, India hits a rocky patch

Arctic summers are short. But when the polar day takes hold in late May, the sun entrenches itself in the skies of the High North for months on end. Under its beams, the Arctic sea ice recedes towards its annual nadir, which opens the region to a short-lived flurry of commercial, naval and scientific activity. This year - according to NASA’s satellite imagery - the Arctic sea ice minimum extent was reached on September 11. At 4.28 million square kilometres, the ice sheet was at its seventh-smallest ever measured since recording began in 1979. Across the decades, the Arctic ice cover has continued to shrink in the average, perhaps irreversibly so. Compared to this simple fact, all other security problems invoked on this blog pale into relative insignificance. Still, they are worthy of discussion.

Photo: Visualisation of the Arctic sea ice on September 11, 2024, with the average minimum extent of 1981-2010 overlaid in yellow (Source: NASA, Trent Schindler)

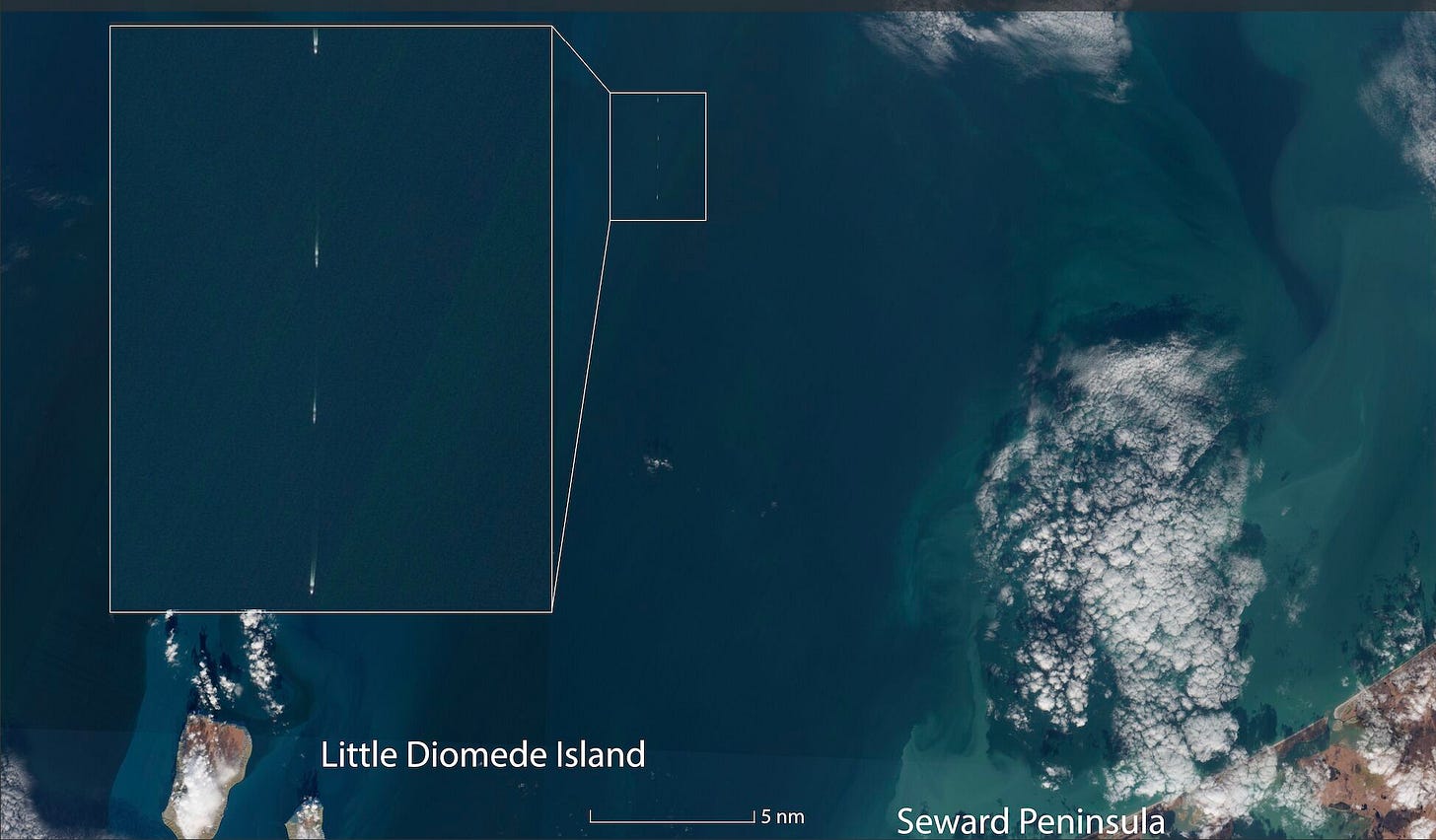

Russia and China in the Bering strait

The end of the summer season brought quite a few notable developments in Arctic security. The glitziest headline of the month, which rapidly proliferated across the planet, focused on the Chinese coast guard’s first-ever forage into Arctic waters. On September 28, the U.S. Coast guard first spotted two Russian border guard vessels and two Chinese coast guard ships approximately 700 kilometres southwest of Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea.

Although some U.S. authors seemingly suggested that this voyage had not been announced, the Beijing ribao (北京日报) already ran an article on the launch of the mission on September 13. According to a military expert quoted by the paper, the Meishan (梅山) and Xiushan (秀山) were “dispatched to the region to practice joint law enforcement capacities” with Russia, especially in the areas of illegal fishing and smuggling. In 2023, China and Russia signed a Memorandum of Understanding on strengthening bilateral coast guard cooperation in the Arctic, which foresees annual joint exercises in the Pacific.

Under the North Pacific Fisheries Commission, a regional fisheries management framework that counts both China and Russia, but also the U.S., Canada, and the E.U. among its members, registered member state vessels are authorised to perform select law enforcement operations in the international waters concerned. The Meishan and Xiushan are both currently listed among member state vessels.

Despite therefore being legitimate in principle, the Sino-Russian joint patrols in the Bering raised many eyebrows on the other side of the Pacific. The Bering strait is a potential geopolitical flashpoint between Russia and the U.S., the Meishan and Xiushan are potently armed, and China openly acknowledged that the mission served the additional purpose of expanding the Chinese coast guard’s overall operational scope. China considers the U.S. coast guard, which only operates under the Navy’s purview in wartime, to be a sixth branch of the U.S. military. In the spirit of superpower competition, China’s own coast guard, it is hoped in Beijing, will grow to match that of the Americans.

Photo: Russian and Chinese coast guard vessels skirt U.S. territorial waters in the Bering Strait (Source: Sentinel 2 image, modified by Malte Humpert for gCaptain)

China and Russia also recently moved to increase the ‘interoperability’ of their navies in a variety of theatres, including during Russia’s “Okean-2024” exercises, which reportedly brought together 400 warships under Russian tutelage (the U.S. Navy operates around 300-400 at any given time). It can thus safely be assumed that the threatening potential of the Bering exercise were not lost on Beijing or Moscow. In reaction, the U.S. coast guard dispatched its icebreaker Healy to Alaska, to counter China’s and Russia’s presence as soon as the vessel was patched up after suffering an engine fire in the summer.

Video: CCTV, China’s national broadcaster, shared pathos-laden images of the mission with it's audiences in the country and beyond

New Nordic bonds and Canada-Russia relations

Threat perceptions regarding China and Russia also continue to shape new alliance building efforts in the western Arctic. For instance, on 17 September, Allied air command general James Hecker spoke of NATO’s plans to create a combined air operations centre for the Arctic, in order to better deal with mounting interceptions of Russian planes in the alliance’s northern airspace. With characteristic measuredness, the news agency RIA Novosti ran a report on Hecker’s comments under the headline “The goals are defined! World War III will not start where everyone expects it to.”

On 20 September, the defence chiefs of Iceland, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden signed a joint defence concept for the Nordic region, which is supposed to facilitate joint military exercises and training, force building and joint operations. The agreement stands within the context of NORDEFCO, a Nordic defence platform founded in 2009, which was recently reinvigorated by an agreement to define shared Nordic defence goals until 2030.

The Nordic states also held their first strategic dialogue meeting with Canada in September, first on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York City, and then in Nunavut. Security issues, including the war in Ukraine and Arctic deterrence, were high on the meeting’s agenda. According to Bloomberg, discussants considered the formation of a new ‘Arctic security group’ to counter Russian and Chinese ambitions in the High North.

Russia - which has itself flirted with alternate alliances and conceptions of Arctic order - reacted viciously to the Nordic-Canadian summit. In an interview with Izvestiya from 3 October, Grigory Karasin, the chairman of Russia’s Federation Council Committee on International Affairs, fumed that “"[…] no alliance for stability and cooperation in the Arctic will be possible without our participation, it is doomed to failure. And, in my opinion, it is frankly provocative. This is clearly a well-thought-out, long-term attempt to provoke tensions in the Arctic as well.”

Andrei Klimov, deputy chairman of the very same committee, aimed his responding salvo directly at Canada. To quote, Canada’s two reasons for seeking security integration with Nordic states in the Arctic were - according to Klimov - A) “its geographical proximity to the Arctic”, and B) Canada’s alleged “indisputable leadership in reheating [sic] Hitlerite Nazis.” Canadians, senator Klimov mused, had “tired of remaining in the media shadow of their anti-Russian colleagues from other Anglo-Saxon communities in Britain and America.”

Photo: U.S. and Canadian claims in the Beaufort Sea (Source: Sovereign Geographic, Inc.)

Canada has become a favourite target of Russia’s rabid pundit class since its parliament - unwisely - gave a standing ovation to a SS Division Galizien veteran roughly one year ago. And Moscow’s dislike of Ottawa’s Arctic policies is unlikely to diminish anytime soon. In late September, Canada and the U.S. decided to move ahead with negotiations on the settlement of the Beaufort Sea Boundary, including the two states’ overlapping Arctic continental shelf claims.

As a non-party to UNCLOS, the U.S. had unilaterally advanced its extended continental shelf claim in the spring, which drew the ire of Russia. It is common practice for Arctic states to negotiate bilaterally over the settlement of maritime boundary disputes, but usually in light of recommendations given by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) in New York. Given the U.S.’ non-adherence to UNCLOS, however, Canada’s decision may arguably be seen as further weakening a treaty regime of which Russia is a vocal proponent. According to Tore Henriksen, a professor of law at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø, by bypassing the CLCS alongside Canada, the U.S. may come to “get the benefits without the obligations” of maritime international law - a point long made, admittedly, by lawyers and diplomats in Moscow.

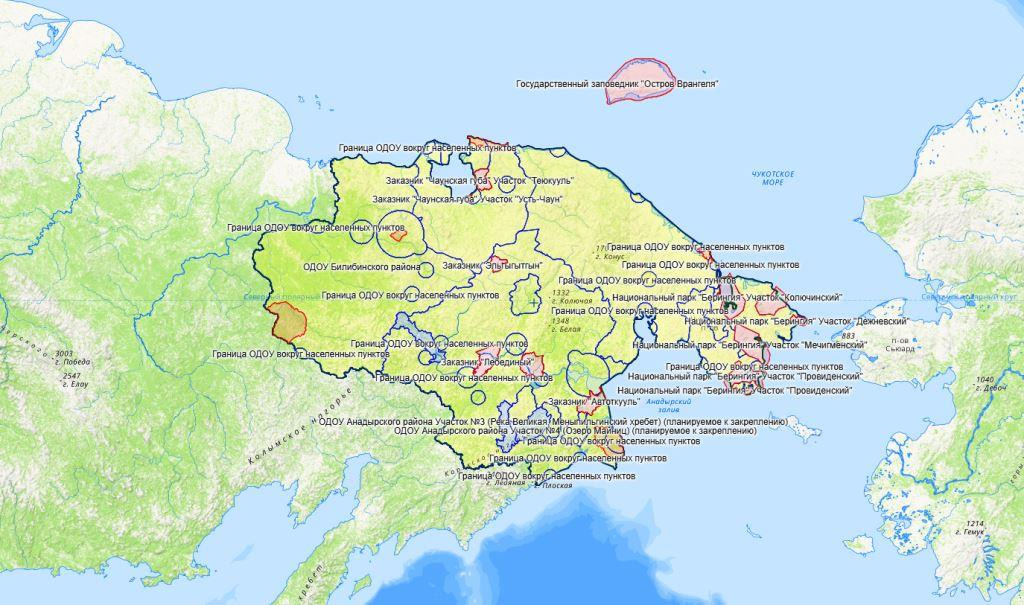

Chukotka and the development of Russia’s Arctic territories

In the Russian Arctic, ambitious plans to push forward with economic development projects remain in place. But as in other areas of the Russian economy, these plans increasingly seem to be implemented on borrowed time.

A large Business Index North report published in September provided many interesting details on Russia’s Arctic investments. Russia is responsible for 50-60% percent of all Arctic investments. 80% of these payments are concentrated in the European Arctic, especially on Yamal and in parts of the Siberian Arctic.

Interestingly, while Russian overall investments into the Arctic fell by 18% between 2017 to 2022, in the same period, investments to the far eastern region of Chukotka grew nearly fourfold. The sleepy region at the far northeastern edge of Eurasia will, it is hoped, become an economic hub and firmly anchor Russia’s Arctic interests on the Pacific side of the region. The recent investment hike is associated in the report with “large projects within mining, especially gold and copper, a floating nuclear thermal power plant, and the Northern Sea Route infrastructure.” From a geopolitical point of view, the explanation for the spending spree is rather banal - Chukotka lies next to the Bering Strait, which is expected by Moscow to become a hotly contested maritime chokepoint in the future. By developing the region, Russia perhaps hopes to create an economic, infrastructural and demographic base for its eventual ‘militarisation’.

Photo: Economic map of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug (Source: huntmap.ru)

A similar logic also applies to Russia’s ongoing ‘Hectare in the Arctic’ (Арктический гектар) programme. Launched in 2021, this government initiative promises up to a hectare of free land to an ever-widening circle of Russians willing to move to and settle in the country’s Arctic territories. According to the Russian authorities, 800 individuals applied for ownership of one such hectare between May and September of 2024 alone. Even if true, this 21st century Virgin Lands campaign is unlikely to fix the long-standing demographic problems of the Russian north. Like much else in Russian politics, the programme seems to have been inspired more by a sense of demographic panic than by practical economic concerns, as has been argued by Kara Hodgson and Marc Lanteigne.

Photo: A probably pretty symbolic image of a home financeable through Hectare in the Arctic’s offshoot mortgage support scheme “Your home in the Arctic” («Свой Дом в Арктике») (Source: арктическийгектар.рф)

In Moscow, bureaucrats in Russia’s Ministry for Emergencies (МЧС) have been readying their megaphones to promote a coastal security mega-exercise coming up in January 2025, which will see security forces from twenty countries, including Vietnam, participate in search-and-rescue drills across ten regions of the Russian north. In the interest of operationalising the Northern Sea Route, the Ministry plans to open four new ‘security centres’ across the Russian Arctic to assure maritime safety. For air rescue operations, seven new helicopter units are supposed to be put in place. The exercises, it is hoped in Moscow, will not only be a boon to Arctic cooperation efforts with Asian states, but also a de facto trade fair to showcase Russian security technologies.

In a similar vein, security representatives of the BRICS states discussed Arctic maritime security with Vladimir Putin at the sidelines of the Russian Energy Week, held in St. Petersburg in mid-September - a conference that also saw the president admit again to the “difficulties” faced by Russia’s LNG sector due to Western sanctions. The word Putin chose should perhaps best be seen as a euphemism, given Novatek’s really rather serious announcement of 23 September that it will be forced to completely revise its plans for a construction of large-scale LNG projects in Murmansk and Sabetta.

Russia-India relations in the Arctic hit a rocky patch

Given China’s reticence to become more entangled in Russia’s Arctic - and thus increase its regional dependency on Moscow - India has recently become an important alternative partner for Russia (I have written about this in the past - here and here).

On the face of it, all this makes much sense. Russia refuses to diversify away from its economic model, which is the export ad infinitum of oil and gas. With European markets closing to it, and China aiming to decarbonise until 2060, Russia needs new buyers for its resources, a vast majority of which are in the Arctic. Enter India - the country has much industrialising left to do, and expects to rely on fossil fuels for longer than other major economies.

Photo: Indian researchers celebrate the country’s independence day in 2017 at the Himadri station on Svalbard (Source: NCPOR on X)

Also, India has potent polar capacities due to its proximity to Antarctica, and a growing interest in Arctic science. The Indian monsoon cycle is linked - via the Himalayas - to Arctic climate patterns, and the melting of the Arctic ice sheet threatens the subcontinent’s coastal megacities. An observer state at the Arctic Council since 2013, India has operated the Himadri research station on Svalbard since 2008. In 2022, the Indian Ministry of Earth Sciences published the country’s first Arctic strategy, outlining its growing range of ambitions in the region.

In principle, India and Russia are thus incentivised to cooperate on Arctic affairs, following the principle of trading investments and energy purchases for access to Arctic governance and technologies already tested by China. This has produced some results of benefit to Russia.

Photo: India’s National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research in sunny Goa (Source: Wikimedia)

For example, India has become a major buyer of rerouted Russian Arctic oil and coal exports. Some of its energy corporations hope to buy shares of Rosneft’s Vostok-Oil project. Convinced of the logistical and agricultural potential of the Russian Arctic, New Delhi and Moscow have used bilateral summits to discuss the dispatch of Indian workers to Russia’s far east and Arctic north under special migration agreements. India is supposed to assist Russia with the building of icebreakers, despite never having constructed any such vessels in its shipyards. In early October, Indian and Russian officials again met in Vladivostok to discuss how best to cooperate on shipping along the Northern Sea Route. Russia also officially invited India to participate in the establishment of a new BRICS-managed research station on Svalbard. And in May this year, Alexander Makarov, the Director of the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute, went to negotiate scientific cooperation proposals with his Indian counterparts at the Indian National Center for Polar and Ocean Research in Goa’s Vasco da Gama.

Increasingly, however, not all is rosy in this budding polar friendship. In July, Prime Minister Modi returned from a visit to Russia without having managed to wrap up the planned Reciprocal Exchange of Logistics Agreement (RELOS), which would have given the Indian navy access to Russian military facilities in the Arctic. Secondary sanctions and the unavailability of impartial consultants have slowed ONGC Videsh’s interest in cooperation with Rosneft. And on 27 September, India’s oil secretary announced that his country would not buy LNG from Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 site due to fear of sanctions.

Like China before it, India is currently learning that Arctic cooperation with Russia cannot be isolated from global geopolitical trends, or the complicated internal politics of the region itself. How Russia responds to it, as well as the western Arctic states, which will hope to freeze Russia out of making Arctic deals with democratic India, remains to be seen. On the sidelines, however, China has quietly signalled through its international propaganda outlet Global Times that it would be interested in trilateral Arctic cooperation with Moscow and New Delhi, especially on shipping - much in keeping, perhaps, with the spirit of “विद्या ददाति विनयं”, an old Sanskrit proverb teaching that “knowledge gives humility.”

Thank you for reading 66° North. If you haven’t yet, please consider to …