As humankind enters what has been called its ‘third space age’, a new race to the heavens unfolds. Space flight is experiencing a renaissance. Private companies spearheaded by Elon Musk’s SpaceX are slashing launch costs, and a range of countries are developing their first own space programmes. Humanity - or, as some might have it, its billionaires - is dreaming of travel to Mars. The great powers are sketching out rival blueprints for manned bases on the moon. Within the internet-driven service sector of the future, space-enabled technologies will power everything, from precision weather forecasts to smart gadgets and self-driving vehicles. And advanced satellites already now allow underdeveloped regions of the planet to skip multiple steps in infrastructure development, connect themselves to the internet, and unlock economic opportunities for billions of aspirational individuals. The successful maintenance of those satellites, as well as the required ground infrastructure, is becoming a crucial - and thus increasingly securitised - asset for states.

Photo: “Поехали!” (read: Poyekhali!) is the Russian for “Let’s go!”. The word was exclaimed by Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, as he was strapped atop a missile and shot into outer space, thus kicking off humanity’s first space race (Source: Design by Liis Roden)

But, alas, as in previous eras, humanity’s triumphant return to space is being overshadowed by its more terrestrial woes. In a mirror, darkly, the conflicts of old are staring back at New Space. The war in Ukraine has demonstrated the degree to which space capabilities feature decisively in modern warfare. Mining companies are targeting resource deposits on the moon. In Earth’s increasingly congested orbits, satellites cluster, vulnerable to collisions, counter-space capabilities and cyber-attacks. And at more than half a century of age, the Outer Space Treaty is creaking under the impact of advancements in military technologies for use in space, as well as a plethora of disputes arising from the conflicts of interest that underpin the nascent, $1.8 trillion space industry.

Photo: The Lumina mine on the Kangerlussuaq fjord in Greenland. The pile in the middle of the photo is anorthosite, a metal required for the construction of manned bases on the moon (Source: ESA)

All this has coincided temporally with the geopolitical transformation of the Arctic. This circumstance would perhaps only matter for exercises in academic comparison - were it not for the fact that the fates of space and the polar regions are intertwined in a very practical sense. For one thing, both are - perhaps incorrectly - considered by some states as ‘global commons’, which lie, irretrievably, beyond any one country’s own sovereign reach. They therefore are facing similar challenges to their governance systems, which increasingly appear fallen out of time and unfit for purpose, as improving technologies make the economic exploitation of both domains more accessible.

But beyond that fact, outer space and the Arctic are also directly linked because many of the ground infrastructures to sustain space operations are physically located above the Arctic circle. Space and its discontents thus feature heavily in the ongoing recalibration of Arctic geopolitics, and vice versa. The key node connecting the two spheres is the global satellite industry.

As Robin Drevet, a spacecraft controller for the interplanetary missions of the European Space Agency, explained to me in a conversation, satellites all travel along different orbits. Two of particularly high interest, the polar and the Molniya orbits, run around the planet’s north-south axis. To control, track, and communicate with satellites that travel on them, communications systems must be located in one of the two polar regions. For that reason, many antennae can be found in Arctic territories, or on Antarctic bases. Not all them are civilian in nature, as polar orbit satellites are of particular use for military and intelligence purposes.

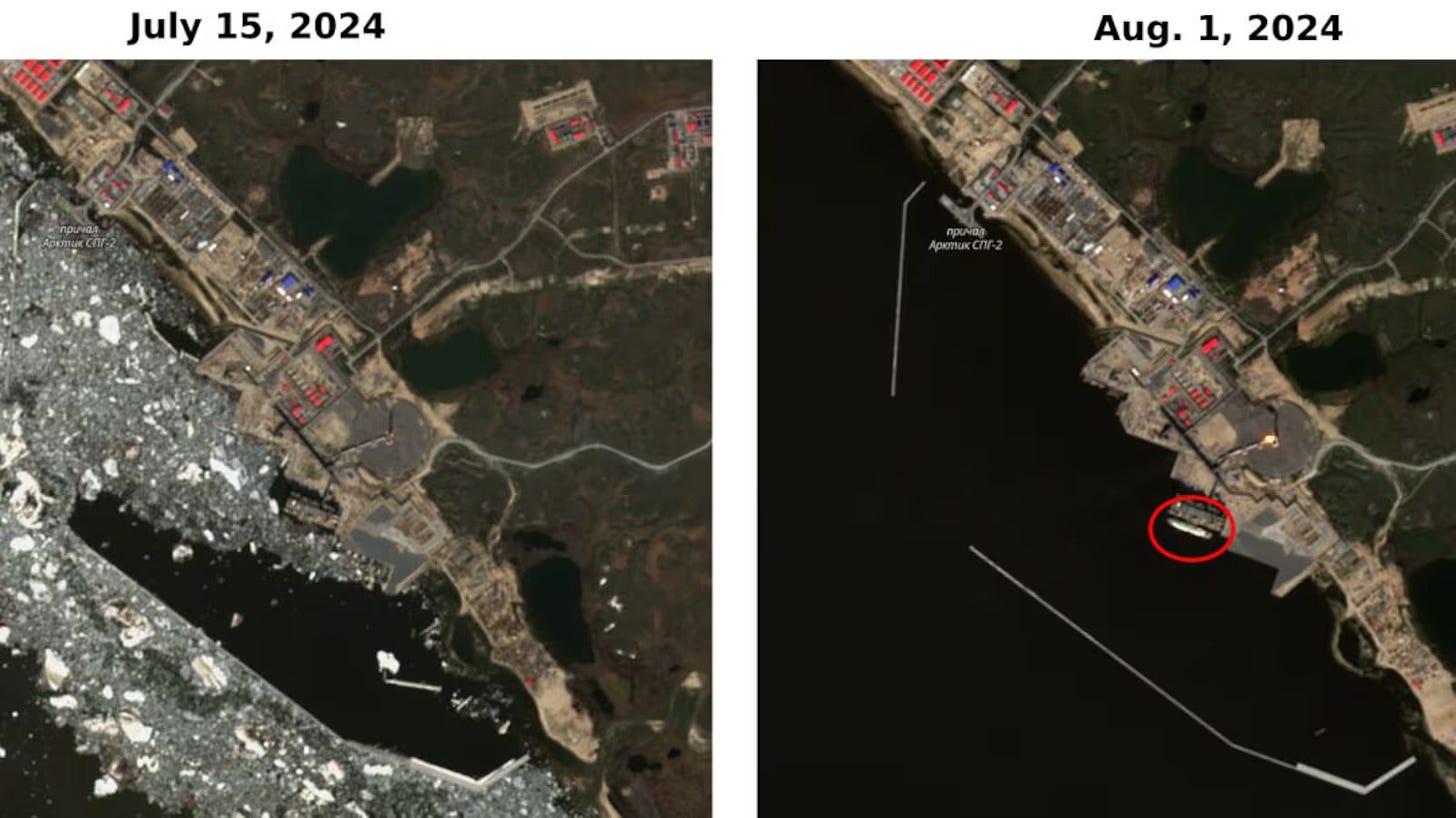

Photo: Satellite surveillance has been crucial in tracking sanctioned Russian energy sites and shipping in the Arctic. These are satellite images of ‘dark fleet’ vessels near Arctic LNG 2, taken by Sentinel 2 (Source: Sentinel 2)

Travelling along the polar orbits permits a satellite to cover all latitudes of the planet, meaning that – at some point – it will pass by any given point of the Earth. This is of particular relevance to the design of satellites tasked with surveillance and the taking of high-resolution imagery. Arctic antennae and command-and-control centres, are thus particularly ‘at risk’ of being co-opted for dual-use purposes.

Installations for data collection are not the only space infrastructure in the Arctic, however. Like the equators, both poles are also well-suited for the launch of rockets. This is because the construction of launch sites at either of the poles allows launchers to optimally harness the rotational force of the planet. For that reason, rocket launching sites are usually located either in the highest possible (read: politically feasible for a state actor) proximity to the equator, such as Baikonur in Kazakhstan or French Guiana - or in the Arctic, as the Antarctic Treaty does not permit for any commercial use of the frozen continent.

Especially since the start of Russia’s assault on Ukraine, there has been a rush among European states to relocate or build rocket launching sites in the Arctic. As EU countries lost access to Russia’s Baikonur site, which they had previously been paying good money to use, alternative installations needed to be provided at speed. The only feasible locations identified were in the Arctic reaches of Scandinavia.

Two projects compete to come first in the new European rocket race: Norway’s Andøya base, and the EU-supported Kiruna launch site in Sweden. Both sites were opened in 2023, and are currently awaiting first launches. An - occasionally not so friendly - competition between both countries over who gets to be the first site to launch a satellite from mainland Europe is in full swing. Although happy news for Brussels and other European capitals, the expansion of the space industry in the Scandinavian Arctic has been criticised strongly by Sàmi villages, who feat the consequences of rocket launches on reindeer husbandry and the sustainability of local ways of life.

Photo: The Esrange Space Centre near Kiruna (Source: SSC)

In other satellite-related Arctic news, three aspects of the U.S. Department of Defense’s recently released Arctic strategy require a further implementation and use of space assets. Firstly, the U.S. military’s new monitor-and-respond approach to Arctic deterrence against Russia and China will necessitate better ground communications for troops, as well as improved reconnaissance and imagery of Arctic territories. Both are only attainable through improved satellite coverage for the North American Arctic. Secondly, recent infractions of the North American airspace, including the infamous Chinese spy balloon incident of 2023, have alerted U.S. decision-makers to the shortcomings of existing air monitoring systems in the north of the western hemisphere. This – thirdly – is also of concern to nuclear strategists, as the U.S. military has identified possible gaps in the early warning missile-radar systems, especially over the island of Greenland. The U.S. military can thus be expected to vastly expand space capabilities in the Arctic, as well as the satellite coverage and internet connectivity of the region. Satellites will likely be launched by Space X. In August, the company already launched two satellites for the U.S.-Norwegian Arctic Broadband Mission. The satellites are designed to provide broadband communications services over the North Pole and high-latitude areas.

Photo: Two GEOStar-3 satellites used for the Arctic Broadband Mission (Source: Northrop Grumman)

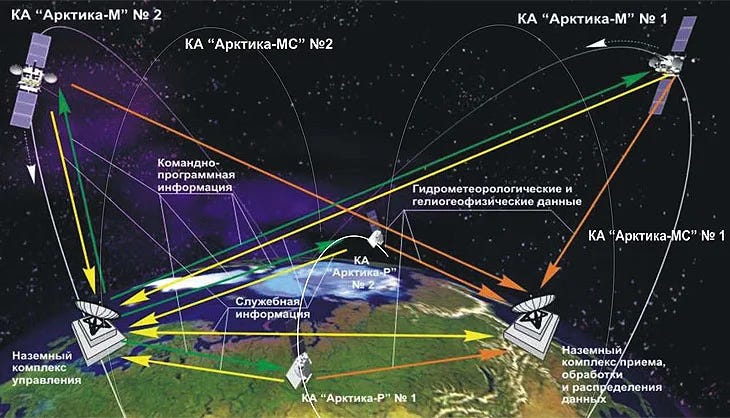

Improved U.S. space capabilities in the Arctic are expected to put Russia in a strategic bind. Moscow is painfully aware that the Russian space sector has fallen far behind. It cannot hope to compete with the U.S. in Arctic aerospace and satellite communications. To compensate, Russia has resolved to projecting air and sea power across its Arctic territories and beyond. But being aware of the military importance of space, Russia has tried to make up lost ground and improve its regional space capabilities. In February 2021, Russia began to improve its Arctic space capacities by launching the first of its Arktika-M satellite. By 2026, Moscow plans to have launched nine additional polar-orbiting satellites to monitor the Arctic. In addition to the checking of hydro-meteorological and environmental conditions, these units will also take images of the Arctic Ocean and the land that surrounds it. Russia needs high-quality images of Arctic waters not only for military purposes, but also to improve the navigability of the Northern Sea Route. For this more commercial aim, Russia has been able to enlist Chinese and Indian assistance. It is possible that these cooperation projects will provide Moscow with military benefits.

Photo: Russia’s Arktika-M constellation (Source: NPO Lavochkin)

As for China, the expansion of its own Arctic space capabilities has required much diplomatic finesse. In the White House’s 2022 Arctic strategy document, Beijing was accused of using “scientific engagements to conduct dual-use research with intelligence or military applications in the Arctic.” In practice, this predominantly refers to Chinese observatories and research stations that are connected to space assets and might serve dual use purposes.

Photo: China’s alleged space projects in the Arctic in 2022 (Source: Voice of America)

Since American attitudes on China’s Arctic presence hardened following Mike Pompeo’s 2019 Rovaniemi speech, and Washington increased its pressure on allies and partners to shut their doors to cooperation with China, Beijing’s land-based Arctic projects experienced notable setbacks. Chinese contracts with Sweden’s Esrange Space Center, for example, were not renewed in 2019, Finland’s Sodankyla Space Campus cooperation project with China was allowed to expire in 2020, and China’s proposed ground station in Nuuk was never approved by the Danish and Greenlandic governments

China has thus been left with few options in the Arctic space domain. Its presence in Svalbard is underpinned by the Svalbard Treaty, and Iceland remains an important diplomatic target for Beijing. But most importantly, as in other Arctic policy realms, China seems increasingly doomed to cooperate only with Russia.

Thank you for reading 66° North. If you haven’t yet, please consider to …

.