New Year’s Eve in Copenhagen is a singular experience. The Danish holiday season is packed with events, from boozy workplace lunches and parties held for the first batches of Tuborg’s Christmas brew to family festivities that stretch across multiple days. Yuletide revelers get only the briefest of digestive respites between feasts of roast pork and duck, caramelised young potatoes, pickled red cabbage, and generous servings of risalamande, a rice pudding topped with chopped almonds and cherry sauce. Come the last day of December, the Danes shake off their collective food coma and prepare to close out the season on a tradition-filled, celebratory hurrah.

Before entire arsenals of amateur fireworks are launched into the capital’s starry skies, however, at six p.m. the streets of Copenhagen fall silent as people gather to watch the New Year’s address of the Danish monarch. This year’s speech had been widely anticipated: Not only was it held for the first time by Frederik X, the new King of Denmark, who in 2024 took over the throne abdicated by his mother, but guests at the party I attended in the modern Sydhavnen neighbourhood also expressed hope that the King might—in one way or another—provide some form of royal guidance on Denmark’s newly precarious international situation.

Image: Screenshot taken from King Frederik’s first new year’s address, 31 December, 2024 (Source: DR1 TV)

As I discussed in my last post for 66° North, U.S. President Donald Trump announced on the 22nd of December that he considered acquiring “ownership and control of Greenland […] an absolute necessity.” By reiterating his desire to bring Greenland under U.S. control before having taken office, Trump set off alarm bells across Nuuk, Copenhagen and Brussels.

While Frederik X did not explicitly mention the United States in his New Year’s address, he stated that “[…] we are all united and each of us committed to the Kingdom of Denmark, from the Danish minority in Southern Schleswig all the way to Greenland. We belong together". A week later, the royal family also ordered a modification of the Royal Arms of Denmark - which now features the insignia of both Greenland and the Faroe Islands in a more prominent position.

Image: The Royal Arms of Denmark, before and after 7 January 2025 - with Greenland represented by a white polar bear (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Trump team, meanwhile, seemed entirely undeterred by rebukes from the King of Denmark, the Prime Minister of Greenland or various Danish government figures. After Erik Jensen, the head of Siumut, Greenland’s social democratic party, invited Trump to visit the island, the President’s eldest son, Donald Jr., took his father’s Trump Force One for a much-publicised blitz visit to Nuuk. On January 7, Trump Jr. and his entourage handed out MAGA hats to a group of passengers in the Greenlandic capital, which reportedly included several homeless folks. The group then took pictures in front of a previously vandalised statue of the island’s original Danish coloniser, Hans Egede, and threw an impromptu party in a local pub - before heading back to the United States.

At a Florida press conference held the same day, Donald Trump announced that he would issue “very high tariffs” against Denmark, should Copenhagen refuse to go along with a U.S. purchase of Greenland. As Denmark is a member of the European Union - which has largely collectivised trade policy - this announcement immediately put both Brussels and major EU member states, such as Germany and France, on notice. Trump also refused to rule out the use of military force in the pursuit of control over Greenland - thereby triggering surreal discussions over legal obligations set by the mutual defence clause (42.7) of the EU’s founding treaty.

On 15 January, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen held a long phone call with Trump on the subject, which the Financial Times reported as having gone “very badly.” Two weeks later, the U.S.’ Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, confirmed to TV host Megyn Kelly that Trump’s Greenland overtures were “not a joke.” In mid-January, the Republican lawmaker Andy Ogles introduced a “Make Greenland Great Again Act” to the U.S. House of Representatives, which is intended to create a legislative basis for an eventual acquisition of the island.

The Greenlandic Prime Minister, Múte Egede, and all five parties in the Inatsisartut, Greenland’s parliament, have emphatically refused to entertain Trump’s overtures, and the Danish government has consistently pointed to Greenland’s right to choose its own future. Still, the U.S. government is now seemingly preparing steps towards a takeover of the island. This situation begs the question of how - if at all - such a takeover scenario could be justified to the international community. Typically, and even in the case of grave violations of international rules on statehood and territorial titles, states make reference to international law in justification of their actions. This is because, according to Martti Koskenniemi, a legal philosopher, international law functions as the “grammar of international relations” - a discursive practice and shared language through which states try to frame their behaviour as lawful, legitimate, or just. Presumably with this goal in mind, Donald Trump openly questioned Denmark’s legal right to sovereignty over Greenland in his press conference on 7 January.

Can the United States “buy” Greenland according to international law?

Contrary to Trump’s comments, however, Denmark’s sovereignty over Greenland is a well-established legal fact. As Ekaterina Antsygina summarised for the European Journal of International Law, the world’s other states have collectively acquiesced to Denmark’s authority over the island ever since Copenhagen fought off a Norwegian claim to Eastern Greenland in 1925. The United States has also consistently recognised Danish sovereignty over Greenland, including through declarations issued in 1916, and supplementary defence agreements concluded in 1941 and 1951. The U.S. and other countries again did so in recognising Denmark’s 2014 submission to the CLCS, and foundational documents of the Arctic Council, including the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration.

At the same time, the fact that Denmark certainly holds sovereignty over Greenland does not imply that its sovereignty is absolute - quite the opposite: In the 18th century, Greenland was forcibly colonised by Denmark. This was acknowledged by the rest of the world when the U.N. General Assembly included the island in its Resolution 1541 - a decolonisation regime negotiated throughout the 1950s, which defines the procedures for colonised territories to gain independent statehood by reference to the principle of self-determination.

Greenland undeniably has the right to self-determination, as a recognised entity separate from Denmark. But while this is true, it is also important to consider the technical modalities of how the island could exercise this right in practice: As Greenland received full constitutional status within the Kingdom of Denmark in 1953, it was taken off the UNGA’s List of Non-Self-Governing Territories, which lists all colonised territories for whom the right to self-determination automatically equates to a right of territorial secession and statehood.

Video: The UNGA of 1960, during which Resolution 1541 containing the rules governing decolonisation was accepted

Unlike in the cases of New Caledonia, Montserrat or Guam, eventual changes to Greenland’s territorial status would not be governed by the UNGA Resolution 1541. Under international law, Greenland’s right to self-determination thus only creates an automatic entitlement to internal autonomy and self-government — but not necessarily full independence. Changes to its territorial status, including either independence, mergers or cessions, would need to be pursued through the domestic legal system of Denmark - which luckily already provides for precisely this eventuality. In 2009, Denmark and Greenland agreed on the Act on Greenland Self-Government, which lays out provisions to specify how the island can claim independence.

As Jure Vidmar explains, Greenlanders would first need to approve an independence agreement negotiated between their government and Copenhagen by referendum. Then, the parliaments in both Nuuk and Copenhagen would have to consent to the agreement. Following independence, Greenland could then - out of its own free will - explore a potential merger with the United States. In absence of Denmark’s consent, however, international law could not be cited in justification of a merger of Greenland with the United States. A “purchase” of territories in the style of the 19th century is clearly not accommodated by the U.N. Charter. And - most importantly, in light of Trump’s recent comments - any coercion on the part of the U.S., the threat or use of force, or outright occupation, conquest or annexation - would render any attempt to absorb Greenland into the United States illegal.

For the United States to “acquire” Greenland in a manner consistent with international law, the island would thus first need to achieve independence - a process for which Denmark will need to be involved, and for which there is significant political support among Greenlanders, but which is also still obstructed by a number of practical roadblocks - including the inability of Greenland’s small economy to generate enough revenue to sustain a capable state apparatus.

While Donald Trump is not known as an ardent supporter of the international order and its rulebooks, he would be well-advised to respect this basic procedural process. This is because not doing so would go against the U.S.’ long-term strategic interest in stable relations with rival ‘great powers’: Any open abandonment by Washington of these most basic principles of international law would throw open the Pandora’s box of territorial irredentism that Vladimir Putin’s Russia already peeked into by means of its territorial conquests in eastern Ukraine.

Should the United States continue to violate the prohibition on the threat of force (UN Charter Article 2.4), or attempt to change the territorial status of Greenland or other entities in contradiction of international principles, this would essentially validate Russia’s nibbling away at Ukraine’s Crimea, or China’s bullying of its smaller neighbours in the South China Sea, in retrospect. This would spell the end of post-war international law as we know it, and thereby wreck one of the most important assets the United States has held in its history as a modern power: an international legal order created in its own image.

Meanwhile, Greenland’s newfound fame has thrown the island’s politics into disarray. In early February, Greenland’s Prime Minister Múte Egede announced snap elections for March 11. The elections are seen as an opportunity for Greenland’s roughly 56,800 citizens to respond to their new circumstances - and will pitch the socialist and pro-independence ruling party, Inuit Ataqatigiit, against its social-democratic coalition partner and rival, Siumut, within one of the most famously left-wing democratic party systems on the planet. Should Greenland ever become a U.S. state with voting rights, it would thus be interesting to imagine the possible impact this would have on the U.S. House and Senate - with the island’s hypothetical representatives likely to push for policies far to the left of those of Bernie Sanders, as was cautiously acknowledged by a report by the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Image: Current distribution of seats in the Greenlandic parliament (Source: Wikipedia)

Alaska’s Mount Denali and the 19th century roots of Trump’s love for tariffs

In another piece of Trump-related Arctic news, the President announced during his inaugural address that Alaska’s Mount Denali would be renamed “Mount McKinley”. The mountain had held that name until 2015, when the Obama administration finally accepted a name change instigated forty years prior by the State of Alaska. The name “Denali”—meaning “Great One”—comes from the language of the Koyukon people, who inhabit the lands around the mountain and have referred to it as “Denali” for centuries.

Image: Mount Denali, now - probably - Mount McKinley (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

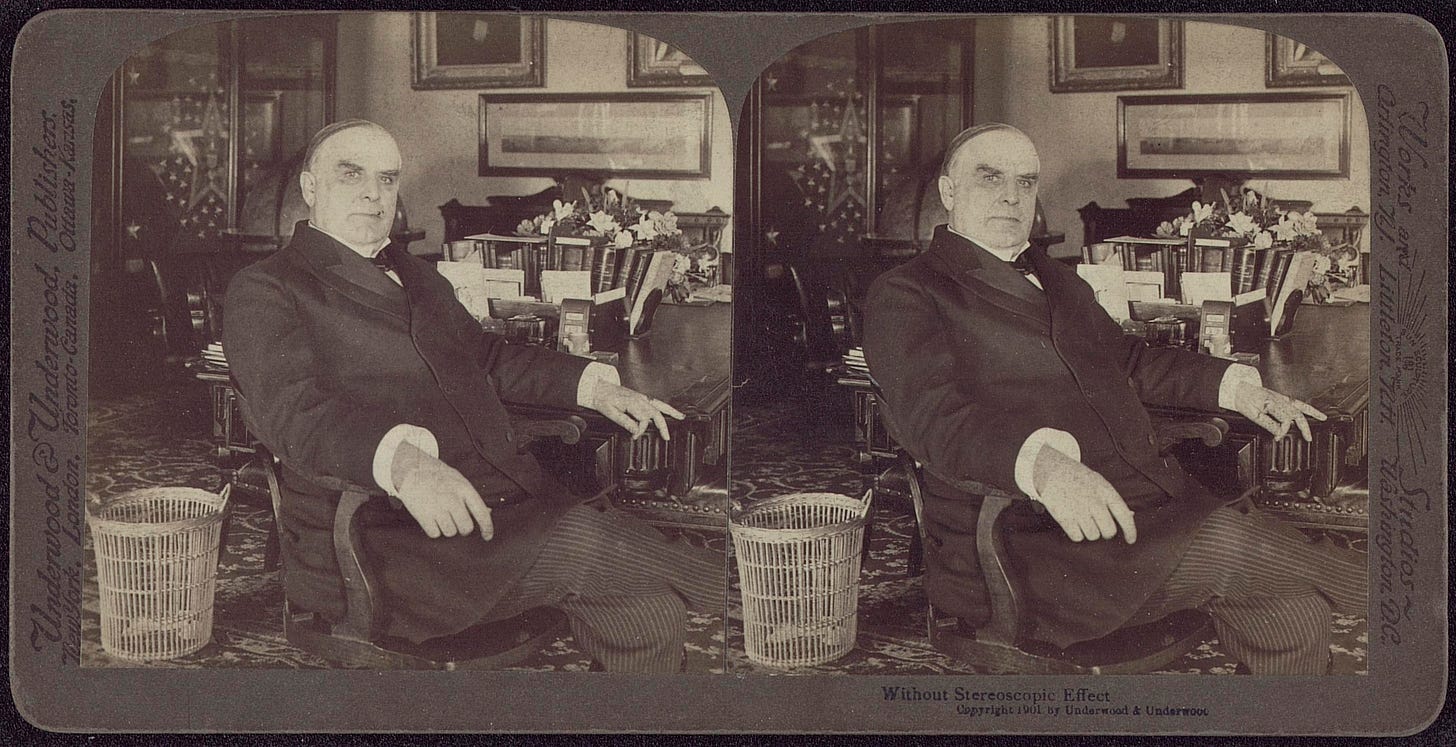

William McKinley, on the other hand, was the 25th President of the United States. He served from 1897 to 1901 and was a territorial expansionist, as well as a major proponent of trade tariffs. During his first term in office, Trump often expressed his admiration for Andrew Jackson, a pioneer of American isolationism. Nowadays, the President seems more inspired by the protectionist legacy and territorial conquests of William McKinley.

On the campaign trail, Trump often pointed to McKinley’s era, the 1890s, as an alleged golden era for the United States, promising that he would seek to emulate the political leadership of the period upon his return to power. In Trump’s reading of McKinley’s economic philosophy, tariffs at the time made America the “proportionally richest country” on earth, and the lives of Americans “sweeter and brighter.”

Image: William McKinley seated in his cabinet room in the White House in 1901 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Historians of the U.S. economy have mostly pushed back against the rosy picture Trump paints of the late 19th century. In a conversation with Conor Lynch of Truthdig.com, the economic historian Jonathan Levy pointed out that McKinley’s era was characterised by devastating economic circumstances, high unemployment and the bankruptcies of small businesses. The “Gilded Age” of the U.S. was—according to Levy and Lynch—marked by “titanic inequalities”, as well as robber barons and other plutocrats.

Corporate and income taxes - which later replaced tariffs as the major source of the U.S. federal budget - were virtually nonexistent at the time. As were most business regulations, environmental standards, or the globalised economy with its complex, integrated supply chains. It is thus not difficult to discern why the McKinley period would appeal to Trump and his inner circle - and why Trump would feel the necessity to restore the 25th President’s name to a major public monument.

The Republican senators of the State of Alaska meanwhile expressed their strong opposition to Trump’s plans: Senator Lisa Murkowski, an avowed opponent of the Trumpian wing of her party, told the press that “[you] can’t improve upon the name that Alaska’s Koyukon Athabascans bestowed on North America’s tallest peak, Denali: the Great One.” Alaska Native organisations have also lodged complaints, and various experts and lawmakers squabbled over whether Trump had the authority to implement the proposed name change.

Canada First?

In another major political development on the North American continent, the political parties of Canada are gearing up for the federal elections. After nine years at the helm of the Canadian government, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is set to step down, leaving behind a shaky legacy, a divided Liberal party, and a country threatened with territorial annexation by its largest neighbour and ally.

A major bone of contention within the Canadian election campaign has been the defence of the Canadian Arctic territories, which I discussed in the December post for 66° North. Candidates have also disagreed over how to deal with Donald Trump’s tariff threats or the U.S. President’s proposal to turn Canada into the “51st state” of his country.

Image: Aggregate opinion polling in Canada as of mid-February (Source: Undermedia - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Among this uncertainty, the Conservative party has emerged as the favourite to lead the next Canadian government. The party’s leader, Pierre Poilievre, is a conservative populist, who wants to crack down on crime, reinvigorate Canada’s sluggish economy through cutbacks on government expenditures and regulations, and stand up to Donald Trump—promising to “put Canada first” in response to Trump’s public jabs.

Speaking in Iqaluit on 10 February, Poilievre announced that he would acquire icebreakers and build a permanent military base in the Nunavut region if he were elected, which would be financed through a drastic reduction of Canadian foreign aid. Canada’s government published a new Arctic Foreign Policy in December, which aims to address the country’s underdeveloped Arctic military capabilities. According to Poilievre and the document’s many critics, the Trudeau government’s plans do not go far enough - especially in light of Donald Trump’s loud criticism of Canada’s low defence expenditures.

Meanwhile, Canada’s Arctic expert community has begun a soul-searching exercise that seeks to understand the implications for the Canadian Arctic of severely degraded U.S.-Canada relations. Frédéric Lasserre of the Université Laval in Quebec published a thoughtful essay, in which he suggested that the dispute between Washington and Ottawa over sovereignty in the Northwest Passage could become much more severe over the coming years. As elsewhere, the national mood in Canada is thus increasingly consumed by trepidation and concerns over basic national security issues.

Thank you for reading 66° North! Please feel free to forward this article, and consider to…

Nice article Lukas! Regarding the liberal perspectives of Greenland you referred to, I wonder what impact that might have on the results of Electoral College votes. Has anyone attempted to estimate how many votes would be allocated to Greenland if Greenland were given voting rights? If the number of votes allocated to Greenland were based on principles similar to those used originally by the founding fathers, then I could imagine Greenland having a number of Electoral College votes equal to or greater than all of the central and midwest states combined. That could mean Greenland could control the US. That’s an interesting thought :)) Perhaps America could be great again.